Does free competition regulate that?

In his new book, Patrick Kaczmarczyck criticizes the hopes for salvation in free competition and calls for an investment offensive by the state. In his contribution he explains how the state can finance these investments.

If we call for a new investment offensive, where will the money for it come from? After all, politicians keep emphasizing that there is no money. The coffers are empty and Corona has only made everything worse. Typical of this way of thinking was ex-Prime Minister Theresa May, when she responded to a complaint from a nurse who hadn't had a pay rise in eight years: 'There's no magic money tree we can shake that's suddenly for everything provides what the people want.«

This is the prime example of a misunderstanding of money that is very common in the public sphere. Where does the money actually come from? Most people take it as income, and so feel like it's something they have to "earn." It would somehow already be there and you have to work for it. In fact, however, all the money in the world is created out of thin air using credit. Yes, every dollar and cent you own is debt created out of thin air. Money is created out of nothing by so-called balance sheet extension: After a credit check, the bank credits the debtor with the desired amount as a deposit using the keyboard, thereby increasing its balance sheet total. We'll come to an illustrative example shortly to make the process understandable.

But first it is important to get rid of misconceptions. Most economics students learn that banks act as intermediaries, lending on existing savings. The Bank of England was one of the first central banks in the world to openly disprove this principle. She clarified that “the reality of money creation today (…) differs from the description found in some economics textbooks. Instead of banks receiving deposits when households save and then lending them, bank lending creates deposits [in the private sector].” The Bundesbank confirmed that the notion that “at the point of lending, the bank acts only as an intermediary occurs, i.e. can only grant credit with funds, which she previously received as a deposit from other customers" was a "widespread error". Likewise, "excess central bank balances are not a necessary condition for a bank to lend (or create money)."

The above statements thus turn the basic tenet of economics on its head, because they imply that – as Schumpeter already pointed out very clearly – savings are not a prerequisite for investing or spending money, but rather the result of previous borrowing. It is therefore wrong when politicians say that one has to save in order to be able to invest. Savings could not be more irrelevant to investment activity. This is not a theory to which one can belong or not. This is simple accounting.

A two tier monetary system

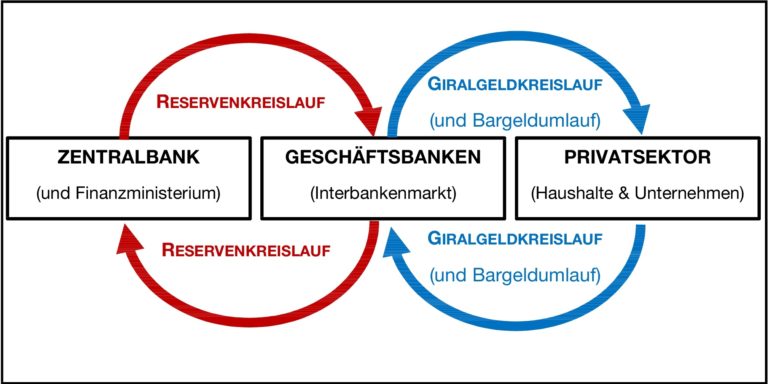

A detailed treatment of the monetary system would go beyond the scope of the book, but a basic understanding is quite helpful. First of all, it is important to understand that the monetary system has two stages or cycles (see figure). On the one hand there is the reserve cycle and on the other hand the bank money cycle. The latter is probably more familiar to most, because in this circuit, money takes the form of deposits in bank accounts (securities) and cash, which are used for day-to-day payments. If you have your deposits in an ordinary commercial bank account and use them to make transfers, or if your employer sends you your salary to this account, all these transfers take place within the bank money cycle. Your transfers reduce the balance of your deposits with the bank and increase them by the same amount for the person receiving your transfer. If you are the recipient, it is the other way around.

In addition to bank money, there is a second cycle in which the so-called central bank reserves assume the money or payment function. Just as you keep an account with a commercial bank, commercial banks keep an account with the central bank. The deposits held by commercial banks in the central bank account are called central bank reserves. The sort code is nothing more than the commercial bank's "account number" at the central bank. The reserves are used in this cycle in order to balance out any payments made by the banks among themselves. Such payments occur when, for example, someone with an account at Commerzbank makes a transfer to someone who has an account at Citibank. In this case, Commerzbank's reserves (assets) are reduced by the same amount as the customer's deposits (liabilities). Citibank, on the other hand, receives the reserves in the amount of the transfer made by Commerzbank, i.e. Citibank's reserves increase and the latter in turn credits the increased deposits to its customers. Normally, banks borrow excess reserves from each other in the interbank market. Should this process come to a standstill, the banks can turn to the central bank, which can then create the required reserves from scratch at the push of a button - no matter what the amount. This means that Citibank's reserve stock increases and the latter in turn credits the increased deposits to its customers. Normally, banks borrow excess reserves from each other in the interbank market. Should this process come to a standstill, the banks can turn to the central bank, which can then create the required reserves from scratch at the push of a button - no matter what the amount. This means that Citibank's reserve stock increases and the latter in turn credits the increased deposits to its customers. Normally, banks borrow excess reserves from each other in the interbank market. Should this process come to a standstill, the banks can turn to the central bank, which can then create the required reserves from scratch at the push of a button - no matter what the amount.

Central bank reserves can also be exchanged by a bank at the central bank for cash that you draw from an ATM. Bank notes may only be created by the central bank, which is why the signature of a Christine Lagarde or a Mario Draghi can be seen on the top left of the euro notes, who direct or have directed the fortunes of the ECB.

Money creation out of nothing

In order to illustrate the process of money creation, we can use a simple example from the bank money cycle - because by far the most money is created in this way. Since we want to try to stay within the framework of a real market economy, i.e. an economy in which the corporate sector plays the role of the investor, let us assume that a given company sees an investment opportunity and wants to take out a loan of 100,000 euros. It goes to the bank. The latter looks at whether the business plan is correct, asks for certain securities if necessary and finally grants the loan. To do this, the bank types the number "100,000" into the computer - and the amount is added to the existing deposits in the company's account.

On one side of the bank's balance sheet, the assets – in the form of the loan – have now increased by EUR 100,000. The liabilities – i.e. the customer’s deposits – increased by the same amount, amounting to EUR 100,000. On the company's balance sheet, it's exactly the opposite. The assets increase by the amount of 100,000 euros, because the company now has this sum in its account to hire new staff, buy machines and so on. On the liabilities side, on the other hand, it is the loan that increases the total liabilities by 100,000 euros. Since only the balance sheet totals increase in the process of money creation, without the need for savings beforehand, lending is referred to as money creation by extending the balance sheet. If the company repays the loan, money is destroyed again. When a government issues money, money is created according to the same principle, although here central bank money is created, in contrast to the bank money created by "normal" lending. In other words, for all government spending and payments to government, we are in the left loop of the diagram (see figure), the reserve loop. With all private expenses and payments, on the other hand, we move in the right cycle, the bank money cycle. Only commercial banks have access to both forms of money. the reserve circuit. With all private expenses and payments, on the other hand, we move in the right cycle, the bank money cycle. Only commercial banks have access to both forms of money. the reserve circuit. With all private expenses and payments, on the other hand, we move in the right cycle, the bank money cycle. Only commercial banks have access to both forms of money.

Now, if the government wants to make an expense — let's say the secretary of defense wants a helicopter that can fly for a change — then the Treasury, which has its account with the central bank, will direct the central bank to reserve the reserve balances of the payee's commercial bank to increase. This means that if Airbus, for example, can build us such a helicopter and the company keeps its account with Deutsche Bank for ethical reasons, then the central bank will credit the Deutsche Bank account with the corresponding amount that is due for the helicopter. You can do this using the keyboard, you don't need to save money beforehand. Deutsche Bank, in turn, adjusts Airbus' account balance accordingly, so that we are again dealing with a simple balance sheet extension: Deutsche Bank now has both higher liabilities (customer deposits) and higher balances (reserves). The state issue thus creates new central bank money and additional deposits. The process always follows the same pattern. As the government purchases goods and services, the reserves are credited to the commercial banks where companies keep their accounts. For the companies themselves, the deposits in their accounts increase. In other words, government spending becomes private sector revenue. As the government purchases goods and services, the reserves are credited to the commercial banks where companies keep their accounts. For the companies themselves, the deposits in their accounts increase. In other words, government spending becomes private sector revenue. As the government purchases goods and services, the reserves are credited to the commercial banks where companies keep their accounts. For the companies themselves, the deposits in their accounts increase. In other words, government spending becomes private sector revenue.

There is no limit to how much money can be created out of thin air, so money shouldn't be called a scarce commodity. Since as much money as needed can be made available at any time at the push of a button, our monetary system is also known as the »fiat system« – derived from the Latin word »fiat«, which means »it will«. Although there is no shortage of money, we do find shortages on the borrower side and on the real resources, goods and services available. There are two extremes here. Either, demand is dead and no one wants to go into debt. In this case we are dealing with a shortage of borrowers. Then no matter how low the interest rate, nobody will invest. The other, but rarer extreme of scarcity is an economy at capacity. That's exactly what we've been seeing since the financial crisis, especially in the eurozone. When capacities are fully utilized, there is a risk of overheating and inflation. However, Europe is very far from such a situation. The scaremongers who paint the specter of inflation on the wall in the EU in the current environment are like those who call out a fire warning during the primeval flood.

All the money in the world is debt

With all the details and the perhaps somewhat unfamiliar mechanisms that make up the modern monetary system, two essential characteristics are absolutely central: 1.) money is not a limited resource and 2.) all money, every cent and every euro in your wallet and on your account, are debts created out of thin air. What is an asset to you is a liability to someone else (either the bank or the central bank). Anyone who would like to cancel all debts in the world would also wipe out the entire money supply.

The fact that there are no upper limits to the money supply has the advantage that liquidity is ensured in a crisis such as the financial or corona crisis. In moments of panic there is always a run on the money and if central banks could not step in, the economy would collapse. The instability and unpredictability of money demand makes it inevitable that the money supply can be flexibly created out of thin air according to demand. If you were to counteract the unstable and volatile demand for money with a stable supply, as demanded by those who dream of a gold-backed monetary system or who see Bitcoin as the solution to all their problems, you would have crazy interest rates and regular liquidity bottlenecks. There is no market economy in the world

The second advantage of the fiat money system is that it gives the state the opportunity to get the economy running again without any problems and completely independent of the level of debt. As long as the government borrows in its own currency and the central bank agrees to buy government bonds, there is not a sum in the world that cannot be paid. The central bank is also the only institution in a market economy that can operate with negative equity. In order to increase public spending, no actor in the economy has to be “burdened”, nor is anything taken away from anyone. From a purely technical point of view, such financing of the expenditure is also not possible,

The question of who is going to pay for the debt, for example in the corona crisis, or how we can start an investment offensive based on the increased debt, is therefore superfluous, because the debt can simply remain on the central bank’s balance sheet. If there are any surpluses at the central bank, these are distributed back to their owner – the state. A government can thus borrow against itself in its own currency, thereby creating wealth in the private sector, and effectively paying itself interest rates, which are set by the central bank and are not dependent on any debt levels.

In the case of a developing country, the mechanism does not work so easily because the developing countries are largely victims of a monetary system that gives them little scope for borrowing in their own currency. Financial market speculation makes it impossible for most developing countries to stabilize the external value of their currency. For the financial markets, on the other hand, speculative transactions and the associated yo-yo games with exchange rates are enormously profitable. For the developing countries themselves, this means regularly recurring currency crises with serious effects on the real economy and development. Without a sane global monetary system, from which we are currently as far removed as from colonizing Mars,

Apart from the scandal that we have not done anything to change this situation for 50 years, it is irresponsible that we do not make use of the advantages of our monetary system in times of the greatest real economic and social challenges, and sometimes with the argument of intergenerational justice is justified. However, both the debts and the assets are passed on to the following generations. Who could blame the latter that they would like to inherit not only greater wealth, but also a solid infrastructure, a good health and education system, and last but not least a habitable planet?

Thanks for writing to us